ISSN: 1130-3743 - e-ISSN: 2386-5660

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14201/teri.31511

BEYOND DEATH EDUCATION? A STUDY OF ITS EPISTEMOLOGICAL TRADITIONS

¿Más allá de la death education? Un estudio sobre sus tradiciones epistemológicas

Agustín de la HERRÁN GASCÓN, Pablo RODRÍGUEZ HERRERO and Victoria de MIGUEL YUBERO

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. España.

agustin.delaherran@uam.es; pablo.rodriguez@uam.es; victoriamiguelyubero@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9156-6971; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2152-0078; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8054-6286

Date of receipt: 14/06/2023

Date accepted: 03/08/2023

Date of online publication: 01/01/2024

ABSTRACT

Death education covers a wide range of fields and contents which, since its beginnings, have included accompaniment, bereavement, and care, mainly from the health sciences. Only in recent decades has it moved into the field of education (education system, schools, training of educators, teaching, etc.), and has been applied beyond the field of bereavement. The best indexed scientific journals on death education define a valid space for two purposes: to know the scientific production in this field, and to recognise contributions made from two epistemological traditions: the Anglo-Saxon and the Central European, of which Spain participates. In the latter, the field (death education) is differentiated from the scientific discipline of reference (Pedagogy of death). The study aims to: (1) describe the publications on death education in quality scientific journals in the last ten years, and (2) analyse and compare the publications on death education from the perspective of the Anglo-Saxon and Central European epistemological traditions. For this purpose, an analysis of scientific production (quantitative and descriptive) has been carried out among the periodicals with the highest scientific impact in the field of death education indexed in the Scopus and Web of Science (WOS) databases from January 2010 to June 2022. Subsequently, a comparative examination of twelve units of analysis from the perspective of both academic traditions has been carried out. The overall intention has been to contribute to the understanding of the literature analysed. It is concluded that the contributions of both educational traditions are enriching, differentiable and complementary. Within the Central European tradition, the publications produced within the framework of the Pedagogy of Death from Spain, associated with the radical and inclusive approach to education, stand out.

Keywords: death; education; death education; scientific journal; Pedagogy of Death; radical and inclusive approach to education.

RESUMEN

La educación para la muerte abarca una amplia gama de ámbitos y contenidos que, desde sus inicios, han incluido el acompañamiento, el duelo y los cuidados, principalmente desde las Ciencias de la Salud. Sólo en las últimas décadas han pasado al campo educativo propiamente pedagógico (sistema educativo, escuelas, formación de educadores, enseñanza, etc.), aplicándose más allá del duelo. Las revistas científicas mejor indexadas sobre death education definen un espacio válido para dos intenciones: conocer la producción científica en este ámbito, y reconocer contribuciones realizadas desde dos tradiciones epistemológicas: la anglosajona y la centroeuropea, de la que España participa. En esta segunda se diferencian el campo (death education) de la disciplina por antonomasia (Pedagogía de la muerte). El estudio tiene por objetivos: (1) describir las publicaciones sobre educación para la muerte en revistas científicas de calidad en los últimos diez años, y (2) analizar y comparar las publicaciones de educación para la muerte desde la perspectiva de las tradiciones epistemológicas anglosajona y centroeuropea. Para ello, se ha realizado un análisis de la producción científica (cuantitativo y descriptivo) entre las publicaciones periódicas de más alto impacto científico en el campo de la educación para la muerte indexadas en las bases de datos Scopus y Web of Science (WOS) desde enero de 2010 hasta junio de 2022. Posteriormente se ha realizado un examen comparativo sobre doce unidades de análisis desde la perspectiva de ambas tradiciones académicas. La intención global ha sido contribuir a la comprensión de la bibliografía analizada. Se concluye que las aportaciones de ambas tradiciones educativas son enriquecedoras, diferenciables y complementarias. Dentro de la tradición centroeuropea destacan las publicaciones realizadas en el marco de la Pedagogía de la muerte desde España, asociadas al enfoque radical e inclusivo de la educación.

Palabras claves: muerte; educación; educación que incluye la muerte; revista científica; Pedagogía de la muerte; enfoque radical e inclusivo de la educación.

1. INTRODUCTION

Interest in death education dates back to the 1920s and 30s in the USA (Rodríguez et al., 2019). With Feifel (1959) it was applied to the training, welfare and mental health of health professionals in contact with death, grief and suffering. Other centres of interest since then have been terminal patient care, suicide prevention, attitude change and fear of death (Zhao et al., 2018). Further pioneers, such as the psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1969), developed our awareness of death through professional health care for the dying in hospitals and hospices.

The main objective of death education is change in the face of death. Feifel (1959) stresses the need to transcend the taboo of death in a multidisciplinary way and foster the awareness of mortality in ourselves and those close to us. This change in attitudes is a key factor in achieving a meaningful, high-quality personal and professional life (Durlak, 1972). As Morgan (1977) remarks:

Death education relates not only to death itself but to our feelings about ourselves and nature and the universe we live in. It has to do with our values and ideals, the way we relate to one another and the kind of world we are building. Thoughtfully pursued, it can deepen the quality of our lives and our relationships (p. 3).

Today, death education encompasses a wide range of educational activities in the areas of death, bereavement, and caregiving. Its formal branch includes academic programs, courses, seminars and clinical practice sessions, all incorporated into the various stages of the education system. As a non-formal activity, it works through “teachable moments” (Eyzaguirre, 2006) which can be exploited for self-education at home or in schools, hospitals, and hospices. The education of children, adolescents and the elderly did not become a field until the 1970s and 80s (Dennis, 2009). Leviton (1977), Knott (1979) and Atkinson (1980) argue for the inclusion of death as a topic in state schools in the USA in the form of objectives, content, guidelines, and resources oriented towards practical knowledge (Berg, 1978; Cordell & Schildt, 1977). Deaton & Morgan (1990) advocate adolescent and youth suicide prevention, intervention and postvention plans. Wass et al. (1990) surveyed a stratified random sample of 423 national state schools, from preschool to twelfth grade, finding that only 11% offered a short course on death as a part of health education, 17 % offered a bereavement education/support program, and 25 % had suicide prevention and intervention programs, while teacher training in the subject was lacking.

Scientific journals have been one of the more notable products of death education, encouraging the publication of quality studies and the advancement of knowledge. Two milestones were the creation of the most important journals in the field: Omega: The Journal of Death and Dying, founded by Kastenbaum in 1970, and Death Education (later, Death Studies), created by Wass in 1977. Although several bibliometric analyses of the topic have been carried out (e.g. Sonbul, 2021), these have focused on quantifying publications but not on identifying different theoretical approaches and their epistemological implications. For this reason, this study aimed to: (1) describe the articles on death education published in quality scientific journals in the last twelve years; and (2) evaluate them from the different standpoints of the English-speaking and Central European pedagogical traditions.

2. METHODOLOGICAL SUPPORT

A valid way to explore the current state of death education is through an analysis of scientific output (quantitative and descriptive). In application of the PRISMA Statement (Page et al., 2021), the following functional information is provided. The search focused on articles in high impact scientific journals, with the descriptor “death education”. The period was January 2010 to June 2022. The reason for choosing this interval was that the inclusion of the last full decade up to the present could reflect the trend of publications on the topic in recent years. The search was conducted in the main databases of the Web of Science (WoS, Web of Science core collection), KCI-Korean Journal Database, MEDLINE, Current Contents Connect, SciELO Citation Index and Russian Science Citation Index) and the Scopus database. The following search filters were used: Subject: “death education”, Years of publication: January 2010 - June 2022, Scopus and JCR Indexing (Sciencce Citation Index-Expanded; the Social Sciences Citation Index; and the Art & Humanities Citation Index). The variables associated with the search for the descriptor and, therefore, the category defining the research corpus (“death education”) were the frequency of production by years, the frequencies of journals publishing studies on the subject, the location of the term “death education” (title, journal, etc.), the categories or sub-areas linked, the frequency of keywords, and the authors with the largest productions. No additional restriction criteria were applied to the publications found.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Academic production in WOS and Scopus

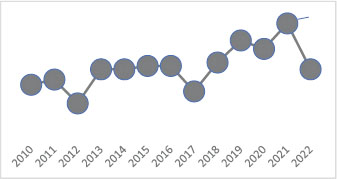

Between January 2010 and June 2022, 520 high-impact articles were published: n = 108 in Scopus, n = 264 in WOS, and n = 148 in both databases. It was observed that, despite occasional dips in the years 2012, 2017 and 2020, there was an overall upward trend in the number of scientific productions on death education (Figure 1). The Covid-19 pandemic declared by the WHO on 30th January 2020 may have had an impact through creating a greater need for knowledge.

FIGURE 1

EVOLUTION OF THE NUMBER OF PUBLICATIONS FROM JANUARY 2010 TO JUNE 2022

Source: Own elaboration according to the databases consulted

3.1.1. Journals

The most productive journal was Omega: Journal of Death and Dying (n = 61), followed by Death Studies (n = 25). Coming far behind these were The Korean Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care and Journal of Palliative Medicine (n = 8, respectively). As can be seen, publications were mainly concentrated in journals in the field of thanatology, encompassing research from different areas of science. A number of health science journals were also found, though with fewer publications. Paradoxically, studies published in journals on the WOS and Scopus education lists were scarce (Table 1).

TABLE 1

NUMBER AND PERCENTAGE OF SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS ON DEATH EDUCATION (≥3)

Journal |

n |

% |

Omega: Journal of Death and Dying |

61 |

28.11 % |

Death Studies |

25 |

11.52 % |

The Korean Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care |

8 |

3.69 % |

Journal of Palliative Medicine |

8 |

3.69 % |

Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial Cooperation Society |

7 |

3.23 % |

Frontiers in Psychology |

7 |

3.23 % |

Handbook of Thanatology: the Essential Body of Knowledge for the Study of Death, Dying, and Bereavement |

7 |

3.23 % |

Korean Journal of Religious Education |

6 |

2.76 % |

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health |

5 |

2.30 % |

Nurse Education Today |

5 |

2.30 % |

The American Journal of Hospice Palliative Care |

5 |

2.30 % |

Indian Journal of Science and Technology |

5 |

2.30 % |

Behavioral Science |

4 |

1.84 % |

Behavioral Science Basel Switzerland BMC Public Heath |

4 |

1.84 % |

Journal of Digital Convergence |

4 |

1.84 % |

Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing (JHPN) |

4 |

1.84 % |

Official Journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association |

4 |

1.84 % |

Korean Journal of Geribtikigucak Social Welfare |

4 |

1.84 % |

The Journal of Learner-Centred Curriculum and Instruction |

4 |

1.84 % |

Final Transition |

4 |

1.84 % |

Theology and Praxis |

3 |

1.38 % |

Gerontology & Geriatrics Education |

3 |

1.38 % |

Journal of Christian Education in Korea |

3 |

1.38 % |

Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing |

3 |

1.38 % |

Korean Journal of Educational Research |

3 |

1.38 % |

Korean Medical Education Review |

3 |

1.38 % |

Studies On Life and Culture |

3 |

1.38 % |

The Journal of Humanities and Social Science |

3 |

1.38 % |

The Korean Journal of Philosophy of Education |

3 |

1.38 % |

Chinese Journal of Practical Nursing |

3 |

1.38 % |

Nursing Education in Thanatology: A Curriculum Continuum |

3 |

1.38 % |

The Thanatology Community and the Needs of the Movement |

3 |

1.38 % |

Source: Own elaboration according to the databases consulted

3.1.2. “Death education” in the title of the journal

Only 2 journals in the Scopus database included death education in their titles: Suicidal Behaviour, Bereavement and Death Education in Chinese Adolescents: Hong Kong Studies and Death Education and Research: Critical Perspectives. The first of these included two articles featuring the keywords “death education”, and the second only one.

3.1.3. Topic categories

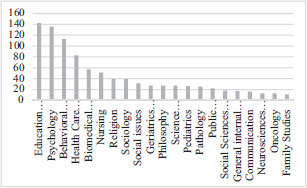

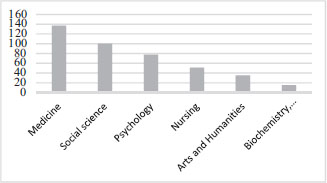

Figures 2 and 3 show the categories with more than ten articles (n > 10) on death education in WOS and Scopus. In WOS, most of the articles were included in the category of Education & Educational Research (n = 142; 15.22 %). The second category was Psychology (n = 136; 14.58 %), followed by Behavioural Sciences (n = 113; 12.11 %) (Figure 2). However, it is important to note that journals with articles on the topic in the Education & Educational Research and Education categories were scarce (e.g. European Journal of Special Needs Education and Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education). In Scopus, most of the articles were included in the category of Medicine (n = 137; 32.93 %). The second-ranked category was Social Science (n = 100; 24.04 %), followed by Psychology (n = 78; 18.75 %) and lastly Nursing (n = 35; 12.26 %; Figure 3).

FIGURE 2

DEATH EDUCATION CATEGORIES IN WOS

Source: Own elaboration according to the databases consulted

FIGURE 3

DEATH EDUCATION CATEGORIES IN SCOPUS

Source: Own elaboration according to the databases consulted

The category of Education in Scopus was not notable for death education. Thus, our data confirmed that in general, the current epistemological and theoretical concept of death education is more akin to the health sciences (medicine, psychology and nursing), where the majority of publications were found.

3.1.4. Keywords

Table 2 lists the keywords of death education articles published in WOS.

TABLE 2

KEYWORDS OF DEATH EDUCATION ARTICLES IN WOS

Keywords |

n |

% |

Humans |

122 |

25.10 % |

Female |

63 |

12.96 % |

Male |

57 |

11.73 % |

Adult |

48 |

9.88 % |

Attitude to death |

48 |

9,88 % |

Young adult |

29 |

5.97 % |

Middle-aged |

27 |

5.56 % |

curriculum |

25 |

5.14 % |

aged |

23 |

4.73 % |

Students nursing |

22 |

4.53 % |

Terminal care |

22 |

4.53 % |

Source: Own elaboration according to the databases consulted

Table 3 shows the keywords of articles on death education published in the Scopus database.

TABLE 3

KEYWORDS OF DEATH EDUCATION ARTICLES ON IN SCOPUS

Keywords |

n |

% |

Human/s |

297 |

22.11 % |

Death education |

156 |

11.62 % |

Article |

103 |

7.67 % |

Female |

89 |

6.63 % |

Male |

83 |

6.18 % |

Adult |

76 |

5.66 % |

Death |

53 |

3.95 % |

Attitude to death |

51 |

3.80 % |

Psychology |

41 |

3.05 % |

Terminal care |

37 |

2.76 % |

Aged |

35 |

2.61 % |

Major clinical study |

33 |

2.46 % |

Middle-aged |

33 |

2.46 % |

Palliative therapy |

33 |

2.46 % |

Bereavement |

31 |

2.31 % |

Education |

31 |

2.31 % |

Palliative care |

30 |

2.23 % |

Young adult |

30 |

2.23 % |

Controlled study |

29 |

2.16 % |

Curriculum |

28 |

2.08 % |

Grief |

24 |

1.79 % |

Priority journal |

20 |

1.49 % |

Source: Own elaboration according to the databases consulted

The keyword “education” only appears on n = 3 occasions in WOS and n = 31 in Scopus. The term “Pedagogy of Death” appears in 8 articles, all of them published by Herrán and Rodríguez, Spanish authors writing in the Central European pedagogical tradition (see Table 4). There were more keywords relating to health and social sciences than to education or pedagogy.

TABLE 4

COUNTRIES AND AUTHORS OF DEATH EDUCATION ARTICLES (WOS AND SCOPUS)

Author |

n |

Country |

Years of publication |

Testoni |

26 |

Italy |

2011 / 2016 / 2016 / 2016 / 2018 / 2018 / 2019 / 2019 / 2019 / 2019 / 2019 / 2020 / 2020 / 2020 / 2020 / 2020 / 2021 / 2021 / 2021 /2021 / 2021 / 2021 / 2021 / 2021 / 2021 / 2022 |

Herrán |

10 |

Spain |

2013 / 2019 / 2020 / 2020 / 2021 / 2021 / 2022 / 2022 / 2022 /2022 |

Rodríguez |

10 |

Spain |

2012 / 2019 / 2020 / 2020 / 2021 / 2021 / 2022 / 2022 / 2022 /2022 |

Kim |

10 |

South Korea |

2014 / 2015 / 2015 / 2016 / 2016 / 2016 / 2017 / 2018 / 2019 / 2019 |

Ronconi |

7 |

Italy |

2016 / 2018 / 2019 / 2019 / 2019 / 2020 / 2020 / 2020 / 2021 / 2021 / 2021 / 2022 |

Zamperini |

7 |

Italy |

2016 / 2016 / 2018 / 2019 / 2019 / 2019 / 2020 |

Ahn |

5 |

South Korea |

2014, 2015, 2016, 2016, 2018 |

Cacciatore |

5 |

USA (Arizona) |

2012 / 2013 / 2014 / 2015 / 2019 |

Doka |

5 |

USA |

2011 / 2013 / 2013 / 2015 / 2015 |

Source: Own elaboration according to the databases consulted

3.1.5. Countries and authors

In WOS, the USA (n = 66 articles) was found to be the most productive country, followed in order by China (n = 44), Spain (n = 30) and Italy (n = 23). Likewise, the USA was the most productive country in Scopus, (n = 94), followed by China (n = 36), Spain (n = 27), Italy (n = 26), South Korea and UK (both n = 21) and Australia (n = 20). The authors with the most articles published in the journals analysed are listed in Table 4, together with their country of reference.

4. THEORETICAL DISCUSSION

Although almost all of the 520 quality publications on death education were in English, they included studies working in differing academic traditions. Here we endeavour to elucidate the two main pedagogical genealogies: the English-speaking educational tradition (EET) and the Central European (or German) pedagogical tradition (CPT). Within the latter, special reference will be made to the case of Spain, due to its importance in the theoretical advancement of death education through the second pedagogical line. The objectives of the comparison were, on the one hand, to gain a greater awareness of the geographical spread of Death Education, from various perspectives; and on the other, to facilitate comparison and contrast between studies in both academic lineages. For the comparative assessment, 12 dimensions were defined.

1. Names and origins of the two educational traditions

The EET is seen here as the tradition emerging in countries and amongst authors of the English-speaking sphere of influence. Its roots are the late 19th-century USA, and it first appeared in the education theory of psychology (behaviourism) and curriculum theory, in the context of the education reforms required for an increasingly industrialized society (Bowen, 1975; Cossio, 2018; Runge, 2013). The most influential author at this stage was Dewey (1902), a representative of progressive education. This tradition later converged with death education, initiated by Feifel (1959) in the 1970s and 80s. By CPT we understand the tradition emerging in countries and amongst authors in the Central European sphere of influence. This line starts in the 17th century with the German thinker Ratke (also called “Didacticus”) and the Czech Comenius (Barnard, 1876; Vogt, 1894), who laid the scientific foundations of modern didactics. A century later, Herbart (2015) achieved the same task with pedagogy as an academic discipline. The first CPT studies on death education (e.g. Neulinger, 1975) were performed in the field of pedagogy.

2. Epistemological identity of death education

In the EET, a multidisciplinary form of death education is advocated (Feifel, 1959), drawing on anthropology, art, literature, medicine, philosophy, physiology, psychoanalysis, psychiatry, psychology and religion. Later, nursing, sociology, history, theology, etc. were added to this list. Pedagogy and didactics are not included, however, since they do not exist as separate academic disciplines in the English-speaking world. In this tradition, according to the Collins Dictionary (2023): “pedagogy” is “the study and theory of the methods and principles of teaching”, while “didactic” (adjective) is defined thus: “something that is didactic is intended to teach people something, especially a moral lesson”, and “didactics” is “the art or science of teaching”. “General didactics”, on the other hand, is applied in curriculum design. In the EET, the field of study (education, death education) is used to refer to both the discipline and the object, a view that is compatible with the multidisciplinary nature of death education (Crase, 1989). The CPT distinguishes clearly between sciences and fields of study. The science of education par excellence is Pedagogy, which exists alongside other education sciences (Durkheim, 2001). Among these we find general didactics, whose object is the study of teaching (Heimann, 1976), learning, training (equivalent to “education”), the curriculum and everything related to these. Neither the English didactics nor the French didactique are equivalent to the German Didaktic (Schneuwly, 2021). When, instead of referring to education in general, pedagogy and didactics refer to forms of education or teaching that take death into account, we can speak of the Pedagogy and Didactics of Death. Thus, these disciplines can be considered branches of pedagogy or general didactics, respectively. In the analysis of scientific production, the keywords “Pedagogy of Death” appear in the articles published by Spanish authors (Herrán and Rodríguez), both working in the CPT. The CPT can also include, although to a lesser extent, works on death education in the health field (mainly psychology) and other sciences.

3. The Pedagogy of Death in Spain and the radical and inclusive approach to education

Spain is a key country in the ongoing definition of the Pedagogy and Didactics of Death. In the last 35 years, Spanish pedagogy has been notable for being one of the most active in publications on death education (Colomo et al., 2023; Jambrina, 2014; Martínez-Heredia & Bedmar, 2020; Rodríguez et al., 2013). Today Spain is the country with the most quality studies on death education in the CPT tradition, as this bibliometric studies shows. Since the 1980s, a number of Spanish philosophers (e. g. Fullat, 1982; Mèlich, 1989) have stressed the need to educate people around the topic of death. Starting in the 1990s, Spanish pedagogue Herrán has been publishing books and essays laying the foundations for the Pedagogy and Didactic of Death from the CPT (e.g. Herrán, 1997; Herrán et al., 2000). In this theoretical current, death is identified as a pedagogical taboo and a “radical topic” (CPT-R), and the Pedagogy of Death is framed in terms of the “radical and inclusive approach to education” (e. g. Herrán, 1993; 2014; 2015), which, while it affords a new perspective, also stems from the CPT. This approach has made a fundamental critique of Western education, which follows the Socratic tradition. A synthesis is advocated of the Western tradition with the teachings of Buddha and the Taoist classics (e.g. Herrán, 2018); he sees the current form of education as necessary, but limited and biased towards the superficial. In the curricula, disciplines and cross-cutting themes (competences and values) are in line with the type of education demanded by society and required by states. They can be complemented by a set of “radical themes” which respond to deeper human needs, but which are currently not respondents, addressed or sufficiently developed in any way by pedagogical theory or expressed by international organizations that condition education. The first of these is topics is death education. The radical curriculum delves into those issues that, by not being treated, show important educational gaps: perennial vital issues, common to all contexts and of a transcultural nature (Herrán, 2022; Herrán & Rodríguez, 2022).

4. Epistemological orientations

The EET line of death education is oriented towards wellbeing and the adaptation of personal and professional life to bereavement, as our analysis showed. While it has developed mainly in the areas of health and the enhancement of the inner life, it can embrace other themes, such as the fear of death (McClatchey & King, 2015), resilience (Kim, 2019), depression (Dadfar & Lester, 2020) and suicide (e.g. Testoni et al., 2020). Although the EET tends to be multidisciplinary, its essential ground is psychology. The CPT line of death education, on the other hand, and its further development into the radical and inclusive approach to education, is based on the Pedagogy and Didactics of Death as scientific disciplines (Herrán y Cortina, 2006); which, although clearly defined fields, are open to complexity and interdisciplinary approaches (Herrán et al., 2000). The appearance of the radical and inclusive approach to education (CPT-R) has produced “epistemological crises” in the normal corpus of Pedagogy and Didactics (Herrán, 2023; Kuhn, 1996; Sankey, 1997).

5. The concept of death education

In the EET, death education refers to all studies on death in society, the training of health professionals, care for the elderly, the dying and the treatment of duel in schools (Crase, 1982; Leviton, 1977). The CPT conceptualizes death education as that which takes death into account in all its aspects (Herrán, 2022): one’s own and others’, formal and non-formal, social and pedagogical, family and curricular, timeless and conjunctural (e.g. due to pandemics, wars, environmental degradation, loss of biodiversity, genocide, extinction, abortion, disappearances of children—kidnappings, accidents, etc.). Epistemologically, it can be defined as an object of study of both the Pedagogy of Death and other sciences that investigate it from their own perspectives. In the CPT-R line, death education is understood as a potential bridge between formal education (both subject-focused and cross-curricular, encompassing competences and social values) and non-formal education, together with other radical educational fields (Herrán, 2022). From a radical and inclusive approach to education, the Pedagogy and Didactics of Death are defined as “disciplines that study education and teaching that include death for a more conscious life” (Rodríguez et al., 2019).

6. The objectives of death education

In the EET, death education aims to improve quality of life through attitudinal, cognitive and behavioural changes by death or in response to death. These changes bring meaning to a life that includes suffering and death (Durlak, 1972). In the CPT, the objectives of death education are to bring the topics of loss, finitude, death and mourning into schools in order to establish death as a normal topic in education and to train teachers in counselling bereaved students through tutoring. In TPC-R, death education aims to foster the inner evolution of the human being through an awareness of death and life, as an education that moves from an immature and egocentric life to a more complex and conscious one, or a personal and social evolution from ego to consciousness (Herrán, 2018, 2022).

7. Participants and target audience population

In the EET, death education is mainly addressed to health researchers and professionals (doctors, nurses, psychologists, etc.) who are in contact with death, dying and bereavement in situations of crisis, catastrophe, terminal illness, suicide and suffering due to the death of loved ones. It´s also addressed to the educational community and society in general. In the CPT and CPT-R, death education is mainly addressed to education researchers, teachers in general, educational counsellors, school heads, politicians in education departments, the media, health professionals and society at large. The main target audience of the TPC-R is people in general, starting with the educational root of all that can be reasoned with, which is each self, and, more specifically, oneself.

8. Approaches and activities in death education

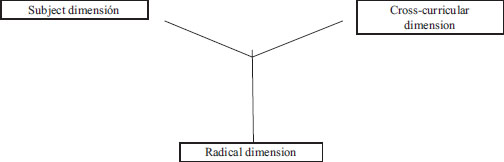

Traditionally, the EET has embraced two distinct approaches (Corr, 2016): the formal or didactic and the non-formal and experiential. However, we prefer to identify three. First, the formal approach, which takes the shape of courses, conferences, lectures, seminars, etc. that aim to promote cognitive enrichment and changes in attitudes. This is put into practice in official degrees, academic programs and specific subjects. For example, in primary and secondary education, university preparation, professional training, etc. The second is the non-formal approach, applied in congresses, meetings, and so on, but also via articles in scientific journals, books, interviews, documentaries, etc., and with the same objectives as the formal approach. Thirdly, there is the non-formal and experiential approach, which is carried out in close personal communication and dialogue based on trust, and includes clinical practice, discussion, exchange of experiences, etc. It is an approach that takes advantage of “teachable moments” (Corr et al., 2000; Leviton, 1977) for self-education at home and in schools, hospitals, hospices, etc., and aims at deeper and more lasting changes in attitudes towards death (Durlak, 1994). All three approaches use audiovisual and other resources. The CPT and CPT-R include two basic didactic approaches (Herrán et al., 2000): before and after bereavement (subsequent approach). The pre-bereavement approach aims to make death a normal topic in education, in curricula and in life in general, through both formal and informal teaching. It is aware that death does not form part of the education required by society, whether subject-based or cross-curricular. In conjunction with other topics and challenges, it embraces a third dimension of the syllabus to give shape to a more educational curriculum (Herrán et al., 2000; Figure 4):

FIGURE 4

3D CURRICULUM

Source: Own elaboration

The post-bereavement approach is identified with tutorial guidance and counselling for the child, student or student group in situations of grief (Herrán y Cortina, 2006). Tutors are links between the school and the family and therefore suitable companions for children/students in this process. They should know: how to coordinate with other teachers; whether they are the most appropriate person to intervene in each case; when to ask for support or to refer the child to a specialist in more complex situations of bereavement (Kroen, 1996), etc. The CPT-R embraces two further approaches (Herrán y Cortina, 2006; Herrán et al., 2000): the phenomenal or evolutionary approach and the meditative approach. The phenomenal approach is associated with the awareness of existing in an evolving universe. From this perspective, death is seen as an evolutionary necessity, with no clearly defined before or after. The atom and the universe participate in this existential, real phenomenon, of which one can also be aware. The fourth is the meditative approach (Herrán, 2021). It has to do with deep or radical education, understood as loss of ego, complexity of consciousness and essential self-knowledge. It draws on the teachings of the Buddha, Bodhidharma and the Taoist classics (e. g. Droit, 2012; Herrán, 2012; Xu et al., 2023) and includes the experience of one’s essential identity or true nature, which has to do with the awareness of non-being, of emptiness, of nothingness, of the non-ego, i.e. the other side of the ego we believe ourselves to be or have identified with and adhered to. The methodology in this approach is meditation (Johnston, 1975).

9. The concept of “death” in death education

The EET centres on a concept of death associated with dying, grief, mourning and loss, broadly understood. On this basis, other concepts, defined by their “preventive” nature (Aspinall, 1996), are seen as part of the life cycle. In the CPT of death education, however, both basic approaches are addressed: loss and grief, on the one hand (e.g., Colomo, 2016), and teaching that embraces death in a natural way on the other (e.g., Colomo & Oña, 2014). The TPC-R identifies 21 different concepts of death (Herrán y Rodríguez, 2020). This divergence and openness of meanings for education multiplies the accessibility of death for educational action.

10. The concept de “education” in death education

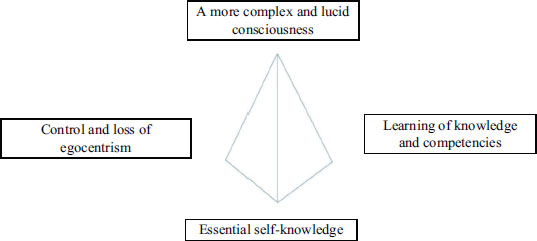

In both the EET and CPT, education is broadly understood as an activity oriented towards skills cultivation, character formation, the learning of disciplinary knowledge, the transmission of the cultural heritage, and the acquisition and development of the competencies and values necessary for democratic, inclusive, critical, creative and participatory citizenship. The CPT-R aspires to a fuller education (Herrán, 2023, 2022, 2021). It is defined as an inner evolution from the ego towards consciousness, which takes place in a complex, non-linear way, and adopts essential self-knowledge as a referent, equivalent to the consciousness of universality (Herrán y Muñoz, 2002). Death education, then, is a bridge through which to arrive at the education of consciousness, which embraces both the EET and CPT understandings of education but which also encompasses other dimensions and radical formative processes neglected by Pedagogy. In this approach, Pedagogy and Didactics include forms of education and teaching based on knowledge, competencies, consciousness and the control, loss and overcoming of self-centeredness with the aim of a more conscious life (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

BASIC MODEL FOR A FULLER FORM OF SELF-EDUCATION

Source: Own elaboration

Within the framework of the radical and inclusive approach, death education is oriented towards educational areas that are simultaneously ancestral, novel and basic, such as ego-loss and control, awareness and essential self-knowledge (Herrán, 1995).

11. The educational effects of death education

In the EET, the main effect of death education is a shift in attitudes towards death, made more effective through the experiential or dialogical approach (e.g. Cordell & Schildt, 1977). In the CPT and CPT-R, educational actions produce changes not only in attitudes, but also in awareness and educational practice itself.

12. The social impacts of death education

The EET of death education is notable for its institutional embodiments; for example, the Association for Death Education and Counseling, ADEC and the creation of departments of health psychology and counselling in high schools and universities in the U.S.A. it also promotes media communications, formal and non-formal events in the education system, courses, lectures, programmes for doctors and nurses, the development of competency benchmarks for educators and trainers in the area (https://www.adec.org/page/Code_of_Ethics#Trainers), etc., including high-quality publications in the fields of psychology, sociology and medicine, in addition to multidisciplinary approaches. While the CPT has fewer social impacts, especially in the formal field, it also fosters events, courses, conferences, guides, research projects, publications, etc.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of the high-quality journals on death education indicates that it is a developing research and training area. Its scientific and professional interest is evident, both in the fields of health and education. Although the focus on death education in health has been going on for a longer period of time, its development in pedagogical systems, contexts and processes is also significant.

Epistemological traditions of death education represent an important dimension to be taken into account in bibliometric, theoretical and empirical studies. Indeed, they help to trace the epistemology of the field. The two traditions analysed (EET and CPT, including CPT-R) differ in several aspects. Most of the quality publications coming from EET refer to professional and social implications of death education, with contents based on Psychology and other Health Sciences. Quality publications in CPT focus more on education, training and teaching that include death, and are assimilated to Pedagogy and General Didactics. Sometimes, because of their novelty and mistakenly, they can be assimilated to health programmes. An example is the project “Caterpillars and colourful butterflies on our desks” (Herrán y Rodríguez, 2020), included in the “School and Health” programme and carried out by the “Canarian Network of Health Promoting Schools” (Spain), also supported by the Pedagogy of Death generated from the radical and inclusive approach to education (Herrán et al., 2000). The CPT and CPT-R publications, which date back to the 1990s and have continued to grow since then -as the study of scientific production shows- define a theoretical approach to death education based on the Central European pedagogical tradition.

An attempt has been made to avoid the error warned against by Kastenbaum (1977): the possibility that education for death would tend towards reduction and epistemological manipulation, as opposed to the open-mindedness of scientific research. In the authors’ view, the present contribution is for openness, as is education, so its sense is consistent with the research. The convergence and synthesis of both epistemological and academic traditions of death education can be a promising avenue for joint scientific development from and for complexity and consciousness, as it is oriented towards the study “of the phenomenon, but of the whole phenomenon”, in the words of Teilhard de Chardin (1955).

REFERENCES

Aspinall, S. Y. (1996). Educating children to cope with death: A preventive model. Psychology in the Schools, 33(4), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6807(199610)33:4%3C341::AID-PITS9%3E3.0.CO;2-P

Atkinson, T. L. (1980). Teacher intervention with elementary school children in death-related situations. Death Studies, 4(2), 149-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481188008252964

Barnard, H. (1876). German Pedagogy. Brown & Gross.

Berg, C. D. (1978). Helping children accept death and dying through group counseling. Personal and Guidance Journal, 57(3), 169-172. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-4918.1978.tb05135.x

Bowen, J. (1975). Civilization of Europe - 6th to 16th century (v. 2) (History of Western education). Routledge.

Colomo, E. (2016). Pedagogía de la muerte y proceso de duelo. Cuentos como recurso didáctico [Pedagogy of Death and the mourning process. Stories as a didactic resource]. Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 14(2), 63-77. https://revistas.uam.es/reice/article/view/3130

Colomo, E., Cívico, A., & Poletti, G. (2023). Analysis of Scientific Production on Pedagogy of Death in the Scopus. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 21(59), 223-250. https://ojs.ual.es/ojs/index.php/EJREP/article/view/7226

Collins Dictionary (2023). https://www.collinsdictionary.com/es/

Colomo, E., y Oña, J. M. de (2014). Pedagogía de la muerte. Las canciones como recurso didáctico [Pedagogy of Death. Songs as a didactic resource]. REICE, 13(3), 109-121. http://bit.ly/3nV7V0E

Cordell, A., & Schildt, R. (1977). Death-related attitudes of adolescent males and females. Death Studies, 2(4), 359-368. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187908253319

Corr, C. A. (2016). Teaching about life and living in courses on death and dying. OMEGA. Journal of Death and Dying, 73(2), 174–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815575902

Corr, C. A., Nabe, C. M., & Corr, D.M. (2000). Death and Dying, Life and Living. (3rd ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Cossio, J. A. (2018). Tradiciones o culturas pedagógicas: del contexto europeo y norteamericano al conocimiento pedagógico latinoamericano [Pedagogical traditions or cultures: from the European and North American context to Latin American pedagogical knowledge]. Actualidades Investigativas en Educ., 18(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.15517/aie.v18i1.31843

Crase, D. (1982). The making of a death educator. Essence: Issues in the Study of Ageing, Dying and Death, 5(3), 219-226. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ264129

Crase, D. (1989). Death education: its diversity and multidisciplinary focus. Death Education, 13(1), 25-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481188908252276

Dadfar, M., & Lester, D. (2020). The effectiveness of 8A model death education on the reduction of death depression: A preliminary study. Nurs. Open, 7(1), 294-298. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.390

Deaton, B., & Morgan, D. (1990). Managing Death Issues in the School. The Office of Public Instruction (Montana). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED361638.pdf

Dennis, D. (2009). The past, present and future of death education. En D. Dennis (Coord.), Living, Dying, Grieving (pp. 197-206). Jones & Bartlett.

Dewey, J. (1902). The child and the curriculum. The Univ. of Chicago Press.

Droit, R.-P. (2012). El ideal de la sabiduría de Lao zi y el Buddha a Montaigne y Nietzsche. Kairós.

Durkheim, É. (2001). Education and Sociology. Free Press.

Durlak, J. A. (1972). Relationship between individual attitudes toward life and death. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 38(3), 463. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0032854

Durlak, J. A. (1994). Changing death attitudes through death education. In R. A. Neimeyer (Ed.), Death Anxiety Handbook: Research, Instrumentation and Application (pp. 243–259). Taylor & Francis.

Eyzaguirre, R. J. (2006). Teachable moments around death: An exploratory study of the beliefs and practices of elementary school teachers. University of California.

Feifel, H. (1959). The meaning of death. McGraw-Hill.

Fullat, O. (1982). Las finalidades educativas en tiempo de crisis. Hogar del libro.

Heimann, P. (1976). Didactics as a teaching science. Klett.

Herbart, J. F. (2015). The science of education: its general principles deduced from its aim and the aesthetic revelation of the world. Leopold Classic Library.

Herrán, A. de la (1993). La educación del siglo XXI. Cambio y evolución humana. Ciencia 3.

Herrán, A. de la (1995). Ego, autoconocimiento y conciencia. Tres ámbitos en la formación básica y la evolución personal de los profesores. Tesis doctoral. UCM. https://eprints.ucm.es/id/eprint/3794/

Herrán, A. de la (1997). El ser y la muerte. Didáctica, claves, respuestas. Humanitas.

Herrán, A. de la (2012). Currículo y pedagogías innovadoras en la Edad Antigua. REICE, 10(4), 286-334. http://www.rinace.net/reice/numeros/arts/vol10num4/art17.htm

Herrán, A. de la (2014). Enfoque radical e inclusivo de la formación. REICE, 12(2), 163-264. http://www.rinace.net/reice/numeros/arts/vol12num2/art8.pdf

Herrán, A. de la (2015). Pedagogía radical e inclusiva y educación para la muerte. Fahrenhouse. https://www.fahrenhouse.com/omp/index.php/fh/catalog/book/19

Herrán, A. de la (2018). Fundamentos para una Pedagogía del saber y del no saber. Hipótese. https://goo.gl/owwaW4

Herrán, A. de la (2021). De la Pedagogía de la muerte a una educación para una vida más consciente. Conferencia. I Congreso Internacional “Hacia una Nueva y Mejor Convivencia”. Ministerio de Educación. Gobierno Regional de Arequipa. Perú. 15-17/12. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AoNrqkyk0Lg&t=47s

Herrán, A. de la (2022). Bases para un sistema pedagógico radical e inclusivo. ¿Irrupción de un nuevo paradigma? Práctica Docente. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 4(8), 61-78. https://doi.org/10.56865/dgenam.pd.22.4.8.197

Herrán, A. de la (2023). Algunas meditaciones para reiniciar la Didáctica General. En A. Medina y A. de la Herrán (Coords.), Futuro de la Didáctica General (pp. 93-215). Octaedro.

Herrán, A. de la, y Cortina, M. (2006). La muerte y su didáctica. Manual para educación infantil, primaria y secundaria. Universitas.

Herrán, A. de la, González, I., Navarro, M. J., Freire, V., y Bravo, S. (2000). ¿Todos los caracoles se mueren siempre? Cómo tratar la muerte en educación infantil. De la Torre.

Herrán, A. de la, y Muñoz, J. (2002). Educación para la universalidad. Más allá de la globalización. Dilex.

Herrán, A. de la, y Rodríguez, P. (2020). Algunas bases de la Pedagogía de la muerte. Práctica docente. Revista de investigación educativa, 2(4), 35-141. https://doi.org/10.56865/dgenam.pd.2020.2.4

Herrán, A. de la, & Rodríguez, P. (2022). The radical inclusive curriculum: contributions toward a theory of complete education. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09810-4

Jambrina, M. A. (2014). Revisión bibliográfica sobre la muerte y el duelo en la etapa de educación infantil [Bibliographic review on death and mourning in early childhood education.]. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(7), 221-232. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3498/349851791024.pdf

Johnston, W. (1975). Silent Music: the Science of Meditation. Harper & Row.

Kastenbaum, R. (1977). We covered death today. Death Education, 1(1), 85-92. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ161925

Kim, J. (2019). Nursing students’ relationships among resilience, life satisfaction, psychological well-being, and attitude to death. Korean Journal of Medical Education, 31(3), 251-260. https://doi.org/10.3946/kjme.2019.135

Knott, J. E. (1979). Death education for all. En H. Wass (Ed.), Dying: Facing the Facts (pp. 385-398). Hemisphere.

Kroen, W.C. (1996). Helping children cope with the loss of a loved one: A guide for grownups. Free Spirit Publishing.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. Simon & Schuster/Touchstone.

Kuhn, T. S. (1996). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Leviton, D. (1977). The scope of death education. Death Education, 1(1), 41-56. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187708252877

Martínez-Heredia, N., y Bedmar, M. (2020). Impacto de la producción científica acerca de la educación para muerte: Revisión bibliométrica en Scopus y Web of Science [Impact of scientific production on education for death: Bibliometric review in Scopus and Web of Science]. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 82(2), 65-79. https://doi.org/10.35362/rie8223553

McClatchey, I. S., & King, S. (2015). The impact of death education on fear of death and death anxiety among human services students. Omega-Journal of Death and Dying, 71(4), 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815572606

Mèlich, J. C. (1989). Situaciones-límite y educación. Estudio sobre el problema de las finalidades educativas. PPU.

Morgan, E. (1977). A manual of death education and simple burial (8ª ed.). Celo Press.

Neulinger, K.- U. (1975). Schweigt die schule den tod tot?: Untersuchungen, fragestellungen und analysen. Manz.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Rodríguez, P., Herrán, A. de la, y Cortina, M. (2019). Antecedentes internacionales de la Pedagogía de la Muerte. Foro de Educación,17(26), 259-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.14516/fde.628

Rodríguez, P., Herrán, A. de la, y Izuzquiza, D. (2013). “Y si me muero… ¿dónde está mi futuro?” Hacia una educación para la muerte en personas con discapacidad intelectual. Educación XX1, 16(1), 329-350. https://doi.org/10.5944/educxx1.16.1.729

Runge, A. K. (2013). Didáctica: una introducción panorámica y comparada [Didactics: a panoramic and comparative introduction]. Itinerario Educativo, 27(62), 201-240. https://doi.org/10.21500/01212753.1500

Sankey, H. (1997). Kuhn’s Ontological Relativism. En D. Ginev, & R. S. Cohen (Eds), Issues and Images in the Philosophy of Science. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, vol. 192 (pp. 305-320). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-5788-9_18

Schneuwly, B. (2021). ‘Didactiques’ is not (entirely) ‘Didaktik’. The origin and atmosphere of a recent academic field. In E. Krogh, A. Qvortrup & S. T. Graf, Didaktik and curriculum in ongoing dialogue (pp. 164-184). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003099390-9

Sonbul, Z.F. (2021). A bibliometric analysis of death education research: 1970-2021. Journal of Theory & Practice in Education, 17(1), 98-113. https://doi.org/10.17244/eku.916222

Teilhard de Chardin, P. (1955). Le phénomène humain. Éditions du Seuil.

Testoni, I., Tronca, E., Biancalani, G., Ronconi, L., & Calapai, G. (2020). Beyond the wall: death education at middle school as suicide prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2398. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072398

Vogt, G. (1894). Wolfgang Ratichius, der Vorgänger des Amos Comenius. Langensalza.

Wass, H., Miller, M. D., & Thornton, G. (1990). Death education and grief/suicide intervention in the public schools. Death Studies, 14(3), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481189008252366

Xu, R., de la Herrán Gascón, A., & Rodríguez Herrero, P. (2023). ¿Qué pueden aportar las enseñanzas de los clásicos del Tao a la educación occidental? Revista de Educación, 399, 105–129. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2023-399-563

Zhao, S., Qiang, W., Zheng, X., & Luo, Z. (2018). Development of death education training content for adult cancer patients: A mixed methods study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27, 4400-4410. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14595